Hi All,

I just thought I would throw some possibly useful information into the record. It might help future members as well as answer some of the questions that have been asked recently in this thread (and others).

When I first got my mechanical valve, it took me a long time to get my INR in range, and it took a larger than typical dose of warfarin to do it.

I was curious to see what the typical warfarin maintenance dose actually was, and where my dose (12.5/day) fell in the distribution. The only paper I could find at the time that had this information was this one:

http://www.futuremedicine.com/doi/ab...7410541.4.1.11

" Individualizing warfarin therapy"

by Kristen K Reynolds, Roland Valdes Jr, Bronwyn R Hartung & Mark W Linder

At the time, I was able to download a free PDF copy of the full paper, but it now appears to be behind a payment firewall.

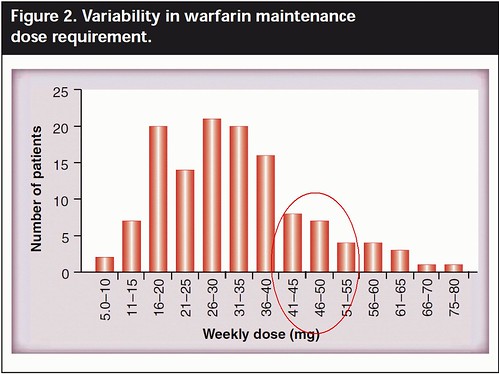

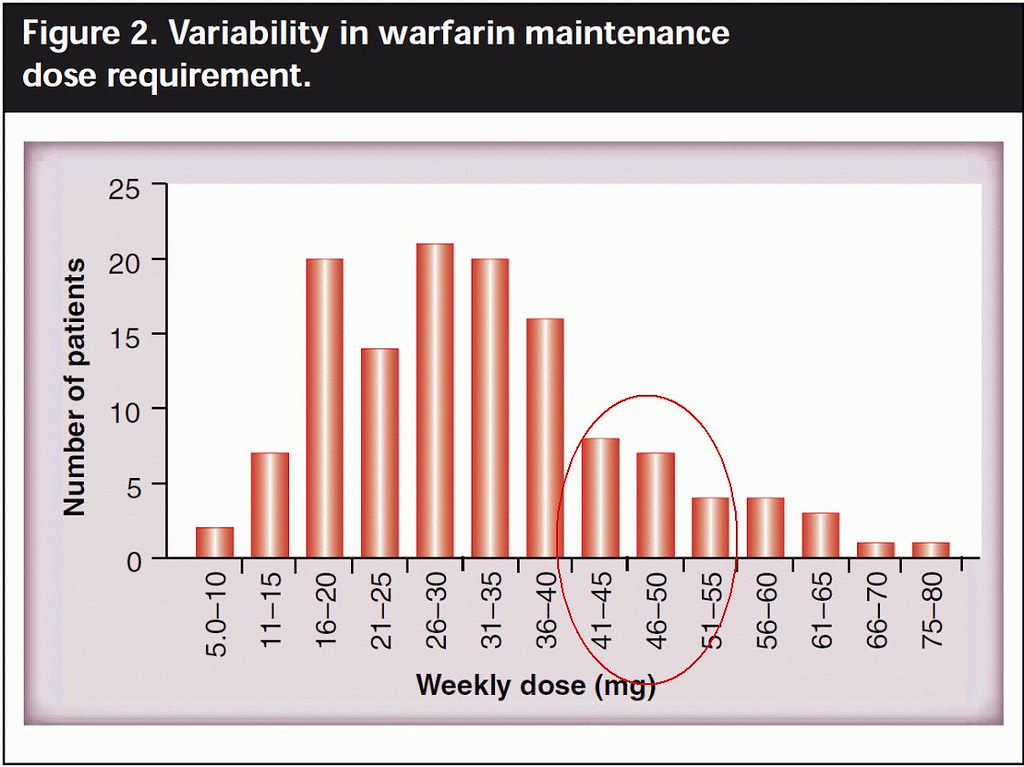

Figure 2 of this paper (shown below) gives the weekly dose distributions from the authors' study of maintenance dose within their sample population.

Figure is at:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B_A...Qjg/view?pli=1 in case it doesn't embed properly in this post.

(Sorry, please use above link to view the figure. I get a "not authorized" error when trying to embed the image)

As you can see, the typical ACT patient seems to average about 5 mg/day which is 35 mg/week.

At 12.5 mg/day (87.5 mg/week) I am off the scale on this chart. So, my own particular maintenance is clearly a 3-sigma case on the high side of daily dose. Nevertheless, this is not any cause for concern. It takes what it takes, and the important measurement is not how much warfarin you take, but rather your INR as a result. At 12.5 mg/day I'm far from setting any records, but clearly anything over 10mg/day would be considered a high dose per this chart.

The paper does make a few interesting points that are a bit technical, but important to note.

1. Our individual response to warfarin is determined primarily by genetics, more so than by age, body weight/size or exercise/activity, although those are also contributing factors.

2. The mechanism that comes into play when you are first adapting to the warfarin and building to a stable blood concentration is controlled by a different genetic factor than the one driving the short-term vitamin-k antagonism process. This explains why it can take some people many days, or even weeks to climb to their final stable warfarin range, while others achieve stability after only a few days. FYI, it took me about three weeks to get into range taking my maintenance dose of warfarin after I had to bridge from some surgery. It also took several weeks to get into range initially.

The short-term INR response to missing a dose (or 2) can be very quick, and much different from the longer term stabilization time - depending on your particular genetic makeup. In my search for a simple dose-to-INR model, I was unable to find a simple 3rd order equation that matched my own short-term INR response to missing a dose (or 2) and subsequent recovery by taking my normal dose (or more).

I concluded that the mechanisms involved are more complex than a simple curve-fitting model can accurately predict.

I did, however, stumble upon this article:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6947/15/7

"A Bayesian decision support tool for efficient

dose individualization of warfarin in adults and

children"

with available Java application for download that implements the set of differential equations described in the paper.

I plan to give that model a try and see if I can find coefficients that will allow me to more accurately match my own particular metabolism's response and model/predict the optimal recovery from any future faux-pas in my ACT.