Since November 2016, the Department of Cardiovascular Surgery of the German Heart Centre Munich has been pioneering a new surgical method to replace the valve.

“We learned the procedure from Professor Shigeyuki Ozaki from Japan, who developed and standardised it. In this method, a new valve is formed from the patient’s own body tissue. The approach over-comes many problems that used to bedevil the valve-replacement procedure, especially in children and young patients,” explains Professor Rüdiger Lange, Director of the Department of Cardiovascular Surgery of the German Heart Centre Munich and Professor for Cardiovascular Surgery at the Technical University of Munich (TUM).

In the conventional approach, patients receive either an artificial valve made of titanium or a biological valve from a cow or pig. However, both methods have disadvantages. In the case of the metal valve, the patient must be put on long-term anticoagulant drugs to prevent blood clots from forming on the implant. Even small wounds then become problematic for the patient, as the blood coagulates more slowly than usual.

The drawback of bovine or porcine valves is that they only have a life span of 10-15 years, after which they must be replaced. In fact, the life span can be significantly shorter in children and young adults with a congenital valve defect due to increased mechanical stress. Consequently, complicated open-heart surgery must be repeated again and again.

The researchers are confident that the valves which are reconstructed from the patient’s own tissue using the Ozaki method are much more durable. “The valve is built up on the patient’s natural valve ring".

"This means that we don’t require an artificial prosthetic ring, which is fixed and immovable. As a result, the mechanical properties of a natural heart valve are largely retained. In addition, it is no longer necessary to administer anticoagulants after the operation,” says Krane, enumerating the advantages of the new method.

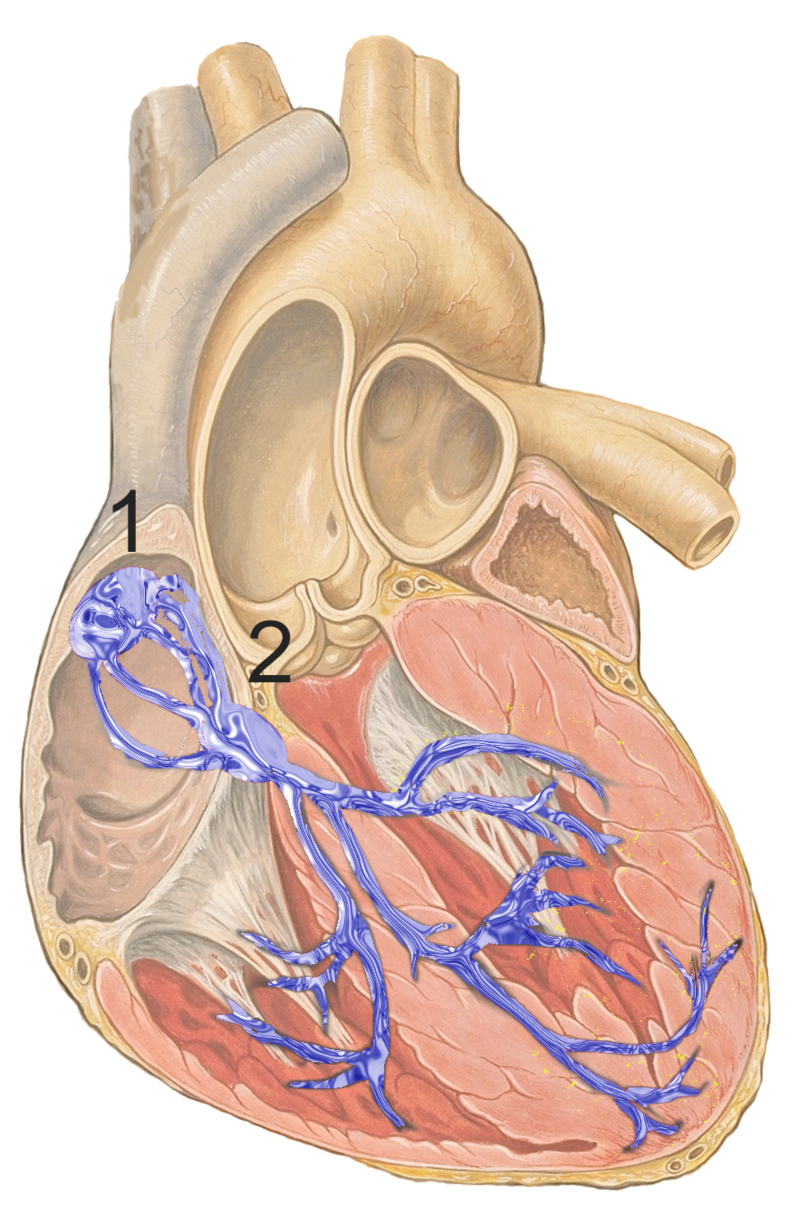

In the Ozaki method, the old defective aortic valve is first completely removed, and the natural aortic valve ring is cleaned. As the human aortic valve consists of three cusps, these three elements must also be reconstructed from the patient’s pericardium, the membrane enclosing the heart.

Markus Krane re-moves a sufficiently large piece from the pericardium, which is then used as material for the new valve. This is not a problem, as the resulting gap is covered at the end of the operation with a piece of synthetic pericardium.

Before the surgeon can use the removed pericardial tissue to reconstruct the aortic valve, it must first be treated. “The tissue is still very soft after it has been removed. In order to be able to use it as a tough, robust valve, we have to tan it by a process akin to the method used for preparing leather,” Krane explains.

As each patient has a different valve size, the surgeons measure the old valve cusps and cut new cusps from the removed piece of pericardium using a bespoke template. The new cusps are then sutured onto the natural valve ring in the patient’s heart.

Krane has already used the new method on over 40 patients – so far without any complications. The re-searchers are currently conducting a clinical trial with over a hundred patients which will run until 2019. They want to determine whether the new approach is superior to the conventional method of replacing a valve with an artificial prosthesis.

“We're trying to show how well the Ozaki method works. Perhaps more doctors around the world will then start using it,” Dr. Markus Krane says. Recently, he introduced the procedure to several Russian doctors with the result that they have now also adopted the Ozaki method.